Multimodal Critical Edition DEMO

This page demonstrates how a digital text of the Regiment could become an interface with Archive materials and other open digital resources, providing readers with an interactive, multimodal representation of the Regiment‘s material and historical context. Ideally, readers would have the option to customize their reading experience by hiding unwanted or distracting features and contributing their own notes, links, images, etc.

Hear these stanzas read aloud:

And opneth his dore and doun gooth his wey.[tippy title=”2″ reference=”https://archive.org/stream/caxtonsgameandp00cessgoog#page/n220/mode/2up”]Compare Hoccleve’s retelling of the exemplum with Caxton’s later Middle English translation of The Chessbook.[/tippy] [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4264.jpg?sequence=3″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] 4265 And aftir blyve out of hir bed they ryse [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4265.jpg?sequence=4″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] 4265 And aftir blyve out of hir bed they ryse [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4265.jpg?sequence=4″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] And cam doun eek. Hir fadir thanken they [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4266.jpg?sequence=5″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] And cam doun eek. Hir fadir thanken they [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4266.jpg?sequence=5″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] Of his good cheere in hire beste wyse – [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4267.jpg?sequence=6″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] Of his good cheere in hire beste wyse – [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4267.jpg?sequence=6″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] And al was for the goldes [tippy title=”covetyse” reference=”http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/m/mec/med-idx?type=id&id=MED10088″ header=”on”]n. Immoderate desire for acquiring worldly goods or estate; covetousness, greed; the acquisitive function of avarice; also, avarice [the fifth deadly sin]; coveiten ~, have a desire or craving. See the full entry in the Middle English Dictionary[/tippy]; [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4268.jpg?sequence=7″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] And al was for the goldes [tippy title=”covetyse” reference=”http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/m/mec/med-idx?type=id&id=MED10088″ header=”on”]n. Immoderate desire for acquiring worldly goods or estate; covetousness, greed; the acquisitive function of avarice; also, avarice [the fifth deadly sin]; coveiten ~, have a desire or craving. See the full entry in the Middle English Dictionary[/tippy]; [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4268.jpg?sequence=7″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] And to goon hoom they axen of him leve; [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4269.jpg?sequence=8″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] And to goon hoom they axen of him leve; [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4269.jpg?sequence=8″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] 4270 They been departed and they there him leve. [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4270.jpg?sequence=9″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

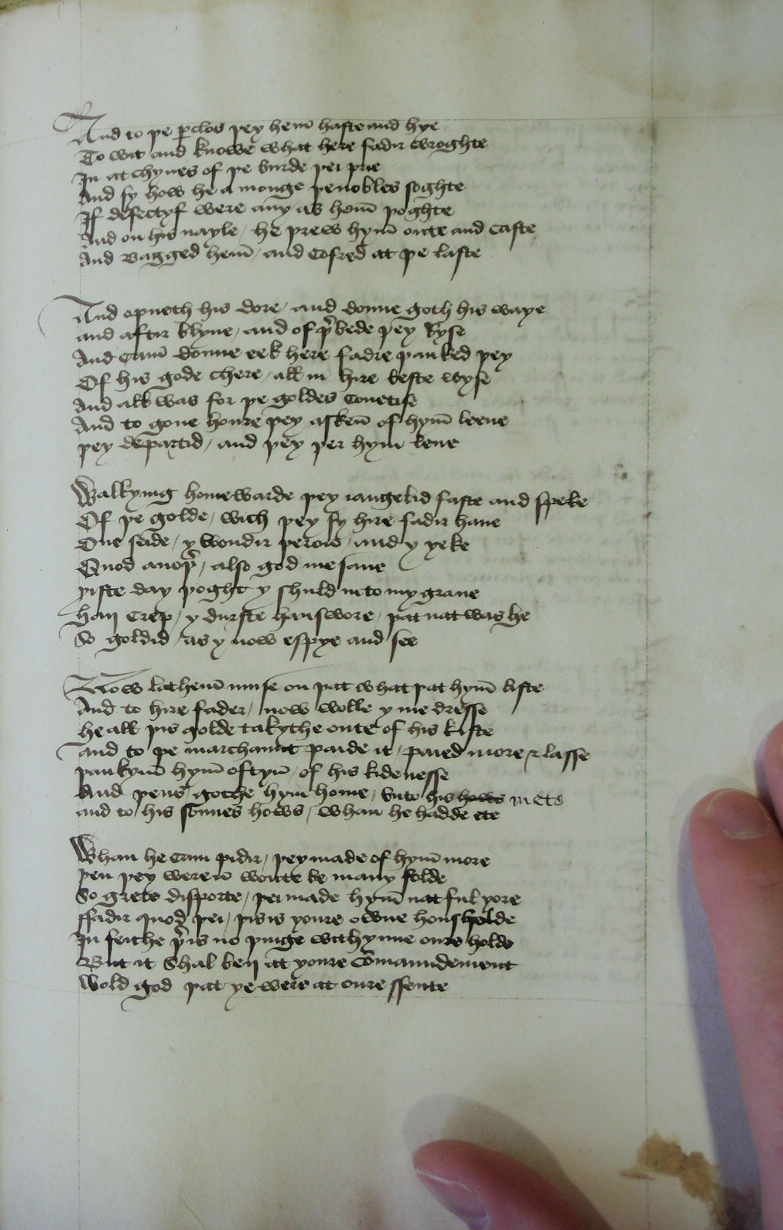

[/tippy] 4270 They been departed and they there him leve. [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4270.jpg?sequence=9″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] Walkynge homward, they janglid[tippy title=”3″ reference=”https://archive.org/stream/caxtonsgameandp00cessgoog#page/n220/mode/2up”]While manuscripts of the poem tended to get more simply decorated over time, punctuation tended to become more actively used in copies throughout the fifteenth century, opening up new ways for readers to interpret vocal demarcation….One rather simple example of this can be seen by comparing the appearance of the stanza of rapid dialogue among John’s children in the tale of John of Canace (RofP lines 4271-7…) in one of the earliest copies of the poem (British Library MS Arundel 38, f.78r) to its equivalent stanza in a late copy of the poem (Newberry Library MS 33.7, f.62r). The stanza in Arundel marks no speaker changes with punctuation, even though tinted and gilded paraphs often mark speaker changes and regularly decorate the beginnings of stanzas throughout the manuscript (…). Newberry, which is much more modestly decorated on the whole, indicates speaker changes in this stanza with virgules, which are used in a manner relatively equivalent to the modern comma (…). The visual distinction between speakers is thus much more pronounced in Newberry. Specifically, the attribution of I-voices in the stanza becomes much less definite compared to Arundel because the virgules offer alternative phrasal breaks that can reshape the clause structure in the syntax: “and y yeke” (at the end of line 3,…) is not necessarily spoken by the same voice as “yiste day þought y shuld into my graue han crep” or “y durste hau swore” (lines 5-6,…). The effect Newberry offers, thus, is much closer to the chattery “jangling” among all four of the people walking home together that Hoccleve describes with the stanza’s first line (…“Walkyng homwarde þey iangled faste and speke”), than the simpler remark and response staged in Arundel’s syntax…. Elon Lang, “Thomas Hoccleve and the Poetics of Reading,” (pp. 86-88)[/tippy] faste and speek [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4271.jpg?sequence=10″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] Walkynge homward, they janglid[tippy title=”3″ reference=”https://archive.org/stream/caxtonsgameandp00cessgoog#page/n220/mode/2up”]While manuscripts of the poem tended to get more simply decorated over time, punctuation tended to become more actively used in copies throughout the fifteenth century, opening up new ways for readers to interpret vocal demarcation….One rather simple example of this can be seen by comparing the appearance of the stanza of rapid dialogue among John’s children in the tale of John of Canace (RofP lines 4271-7…) in one of the earliest copies of the poem (British Library MS Arundel 38, f.78r) to its equivalent stanza in a late copy of the poem (Newberry Library MS 33.7, f.62r). The stanza in Arundel marks no speaker changes with punctuation, even though tinted and gilded paraphs often mark speaker changes and regularly decorate the beginnings of stanzas throughout the manuscript (…). Newberry, which is much more modestly decorated on the whole, indicates speaker changes in this stanza with virgules, which are used in a manner relatively equivalent to the modern comma (…). The visual distinction between speakers is thus much more pronounced in Newberry. Specifically, the attribution of I-voices in the stanza becomes much less definite compared to Arundel because the virgules offer alternative phrasal breaks that can reshape the clause structure in the syntax: “and y yeke” (at the end of line 3,…) is not necessarily spoken by the same voice as “yiste day þought y shuld into my graue han crep” or “y durste hau swore” (lines 5-6,…). The effect Newberry offers, thus, is much closer to the chattery “jangling” among all four of the people walking home together that Hoccleve describes with the stanza’s first line (…“Walkyng homwarde þey iangled faste and speke”), than the simpler remark and response staged in Arundel’s syntax…. Elon Lang, “Thomas Hoccleve and the Poetics of Reading,” (pp. 86-88)[/tippy] faste and speek [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4271.jpg?sequence=10″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] [tippy title=”G” header=”off” ]S12: at STANZA 611, l.4271: RMG: Nota bene nota[/tippy] the gold which they sy hir fadir have. [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4272.jpg?sequence=12″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] [tippy title=”G” header=”off” ]S12: at STANZA 611, l.4271: RMG: Nota bene nota[/tippy] the gold which they sy hir fadir have. [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4272.jpg?sequence=12″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] Oon seide, “I wondre theron;” “And I eek,” [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4273.jpg?sequence=13″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] Oon seide, “I wondre theron;” “And I eek,” [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4273.jpg?sequence=13″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] Quod anothir, “for also God me save, [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4274.jpg?sequence=14″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] Quod anothir, “for also God me save, [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4274.jpg?sequence=14″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] 4275 Yistirday, thogh I sholde into my grave [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4275.jpg?sequence=15″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] 4275 Yistirday, thogh I sholde into my grave [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4275.jpg?sequence=15″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] Han crept, I durste on it han leid my lyf [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4276.jpg?sequence=16″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] Han crept, I durste on it han leid my lyf [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4276.jpg?sequence=16″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] That gold with him nat hadde be so ryf.”[tippy title=”4″ reference=”https://archive.org/stream/caxtonsgameandp00cessgoog#page/n220/mode/2up”]Newberry’s variant reading of lines 4276-7 (…) also eliminates the Arundel speaker’s comment: “I durste on it han leid my lyf / That gold with him nat hadde be so ryf,” which follows from the image of “having crept into my grave” present in both manuscripts. Newberry’s replacement: “y durste hau swore / þat nat was he // So goldid / as y now espye and see,” emphasizes the speaker’s own direct visual observations of John and his gold with the end-rhyme of the final couplet in the stanza that juxtaposes what the speaker saw (“he”) with his act of surveillance (“see”). The Newberry version also simplifies the speaker’s mode of swearing disbelief, syntactically separating the “crept into the grave” expression from the “I would have sworn” remark by stripping out the second clause’s pronoun reference to the grave. This “edit” portrays a more independent expression of surprise that once again encourages the sense that more than two voices could be speaking in the stanza. The fact, too, that the Newberry version is replicated in more surviving Regiment manuscripts than the Arundel version,70 suggests that more readers may have perceived more voices in the text from their copies than Hoccleve may have initially designed in the punctuation of his first presentation copies. However, these readings also put a greater emphasis on the personal observation and interpretation of John’s deceptive performance and would have amplified Hoccleve’s overall portrayal of readers’ authority that stems from the depiction of voices in the tale. Elon Lang, “Thomas Hoccleve and the Poetics of Reading,” (pp. 86-88)[/tippy] [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4277.jpg?sequence=17″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] That gold with him nat hadde be so ryf.”[tippy title=”4″ reference=”https://archive.org/stream/caxtonsgameandp00cessgoog#page/n220/mode/2up”]Newberry’s variant reading of lines 4276-7 (…) also eliminates the Arundel speaker’s comment: “I durste on it han leid my lyf / That gold with him nat hadde be so ryf,” which follows from the image of “having crept into my grave” present in both manuscripts. Newberry’s replacement: “y durste hau swore / þat nat was he // So goldid / as y now espye and see,” emphasizes the speaker’s own direct visual observations of John and his gold with the end-rhyme of the final couplet in the stanza that juxtaposes what the speaker saw (“he”) with his act of surveillance (“see”). The Newberry version also simplifies the speaker’s mode of swearing disbelief, syntactically separating the “crept into the grave” expression from the “I would have sworn” remark by stripping out the second clause’s pronoun reference to the grave. This “edit” portrays a more independent expression of surprise that once again encourages the sense that more than two voices could be speaking in the stanza. The fact, too, that the Newberry version is replicated in more surviving Regiment manuscripts than the Arundel version,70 suggests that more readers may have perceived more voices in the text from their copies than Hoccleve may have initially designed in the punctuation of his first presentation copies. However, these readings also put a greater emphasis on the personal observation and interpretation of John’s deceptive performance and would have amplified Hoccleve’s overall portrayal of readers’ authority that stems from the depiction of voices in the tale. Elon Lang, “Thomas Hoccleve and the Poetics of Reading,” (pp. 86-88)[/tippy] [tippy title=”VT” header=”off” reference=”http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/25105/table4277.jpg?sequence=17″ width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] View the manuscript text of these stanzas: | [tippy title=”Newberry Library MS 33.7,Folio 62 recto” width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] View the manuscript text of these stanzas: | [tippy title=”Newberry Library MS 33.7,Folio 62 recto” width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] | [tippy title=”Bodleian Library MS Bodley 221, Folio 118 recto” width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] | [tippy title=”Bodleian Library MS Bodley 221, Folio 118 recto” width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy] | [tippy title=”Bodleian Library MS Laud Misc 735, Folio 118 verso” width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.

[/tippy] | [tippy title=”Bodleian Library MS Laud Misc 735, Folio 118 verso” width=”550″ height=”854″]Click here to open this image in a new tab.  [/tippy]

[/tippy]